In response to a recent email, I received several notes saying, “I didn’t sign up for your newsletter to hear about your political views.” I get that.

Yet to separate integrative, mind-body approaches from politics sets up a false division between them. I’d like to explain why that is—and how it has a negative impact on well-being. Let’s start with the body.

Why Integrative Therapies are Inherently Social (and Political)

From personal feelings like anger or sadness to social emotions like shame or trust, emotions have their origin as sensations in the body. As this origin story begins, receptors in your skin and internal organs collect information. These receptors specialize in distinct sensations: the speed of your heart, the pace and depth of your breath, hunger or fullness, warmth or coolness, activity or soreness in your muscles, emptiness or fullness in your abdomen (and bladder and rectum), and sensual or sexual touch. Once they’ve gathered this intelligence, your sense receptors send it along distinct spinal routes to the brain.

The experience is also brought to you by part of your brain called the insula. In humans (and some mammals), a unique body-to-brain communications network allows the gut, heart, and lungs to mediate information about the body’s inner state. Then, they relay this information to a newly expanded region in the right front part of the insula. Here, simple body states are reinterpreted as complex social emotions. A lingering touch from a partner becomes the feeling of desire. Witnessing someone in pain engenders empathy. The sights, smells, and sensations linked to using a substance elicit cravings.

Thanks to a specialized group of nerve cells called spindle neurons, the link between body, emotion, and society grows even stronger in humans. Spindle neurons cluster abundantly in our body intelligence centers, including the right front portion of our insula. These high-speed communicators have a hand in social interactions, emotional processing, decision making, and intuition. Spindle neurons sense social emotions such as gratitude, pride, distrust, contempt, and empathy. They play a role in the guilt we feel when we’ve hurt someone and the efforts we make at atonement. They let us know when we’ve fallen in love with the person we’re dating. They even help us discern whether something’s amiss with that offer from a new business partner. And they factor prominently in the visceral response we have to matters of social justice.

Why This Matters

These evolutionary adaptations confirm the fact that the body’s power and intelligence extend far beyond its physicality. We have a bodily self, one which is inherently emotional, social, and—yes—political.

Our ability to receive, appraise, and respond to these sensations is known as interoception. (Of course, there’s more to being embodied than interoception, but we’ll focus here for now.) Interoception prompts you to take a bathroom break before it’s too late, registers the soreness in your legs after a long run or session of squats, and lets you feel pleasure at the affectionate touch of a friend. (You can read more about interoception here.) What’s more, the acuity with which we read our bodies determines how we regulate our emotions and relate to others. Our bodily self is critical to our well-being; research shows that when our sense of our body is compromised, we suffer physically, emotionally, and socially.

How This Impacts our Health

What arises when you contemplate the fact that your body is not just physical, but emotional and social and yes, even political? Does this insight feel threatening? Freeing? What do you feel, and where? A woman in a workshop I taught on embodiment described the sensation of excited fluttering in her throat and bronchial area, as though a bird were flapping its wings and trying to get out. What do you feel, and where? (Our minds are trained to rule over somatic explorations such as this; each time you feel your mind attempt to explain, understand, or interpret what you’re experiencing, it helps to return to sensation.)

This expansive view of the body brings with it the gift of new insight into emotional well-being.

Historically, we have believed that illnesses like anxiety, depression, and chronic pain were purely mental or biochemical or brain-related. And yet, these illnesses share a variety of anomalies in our capacity to read our bodies. People with depression, for example, have lower levels of interoception. They don’t sense their bodies fully, and are often less accurate than others about what they do sense. (Furthermore, this lowered accuracy in body sensing correlates with a reduced intensity of positive emotions, suggesting that interoception might strengthen our capacity to experience joy.)

Modern Western forms of wellness (and, let’s face it, popular thought) tend to privilege the mind and marginalize the body. Yet sensing our bodies and expanding our capacity to receive and respond to uncomfortable sensations builds sensory resilience, which “trickles up” to the brain and—no translation required—becomes emotional resilience. In this way, working with body sensations (even uncomfortable ones) is a training ground for mental, emotional, and social well-being. Who among us couldn’t use more of that?

The revelation: Our mind is not the only node of transformation. Training our body can change our mind, brain, and society. This gives us a place to ground our practice in a rapidly changing, volatile world.

The Body and Social Inequity

Let’s consider another reason why integrating practice and “politics” works.

A definition of politics includes “the set of activities that are associated with making decisions in groups, or other forms of power relations between people, such as the distribution of resources or status.” (Thanks, Wikipedia.) And our body is the nexus of power relations, resources, and status.

Consider the news lately: the COVID-19 pandemic, systemic racism and prejudice, school shootings, domestic terrorism, sexual harassment and assault, the erosion of abortion rights, mass incarceration and police violence, the separation and abuse of undocumented families and children, science denial and climate crisis, and the undermining of democracy and equity worldwide. What all these power dynamics share in common: they are wrought on the battleground of the body.

Ta-Nehisi Coates states, “Disembodiment is a kind of terrorism, and the threat of it alters the orbit of our lives and, like terrorism, the distortion is intentional.” Coates speaks here of forced disembodiment, the primary means by which dominant cultural groups acquire people and maintain power over others for social, political, and financial gain. (See Coates’s best-selling book Between the World and Me.)

Think of the ways that dominant culture forces boys and men of color to limit body movement and how they speak or dress to make themselves appear less threatening, reduce the risk of police brutality, and ensure their safety. Or how women compress their bodies to occupy less space, or change their walking routes to avoid potential hecklers, or can’t leave a drink unattended at a bar because it can be spiked. Or the ways in which people with disabilities face body erasure in a world that prioritizes able bodies. (For more about the accessibility movement in yoga, see the work of Jivana Heyman and colleagues.) These examples of forced disembodiment might just seem social and political. And yet, they relate directly to our bodies. They are examples of how proprioception, our sense of our movements and the way we occupy our personal space and the peripersonal space around us, is affected by our social and political world.

Forced disembodiment attacks not just the body’s physicality but its power, presence, and awareness, and the damage trickles through to every aspect of our lives. Embodiment, then, becomes an act of reclamation and resistance.

Our body is as social as it is personal, as public as it is intimate. Human rights are body rights; social justice is body justice.

Any practice that involves mind-body medicine—and this includes yoga, mindfulness, embodiment, psychology, spirituality, and wellness—is also social and political.

Stress Reduction vs. Stress Resilience

Many people want their yoga (or mindfulness or wellness or embodiment) practices to serve as a “respite” from the stress of today’s world. I get that. At the same time, this is a stress reduction strategy. It predicates well-being on the ability to control our environment by removing anything that causes stress. Over time, this is harmful to the health of our nervous (and immune) systems, which not only thrive on but require stress in order to survive. The alternative: A stress resilience strategy which incorporates all experiences, even the ones that stress us out.

The term “respite” derives from the Latin respectus (Don’t you love that?), which means consideration, regard, and literally, “the act of looking back (or often) at one.” We have a lot to look at; and in the long run, doing so builds our stress resilience.

Let’s Translate This into Practice

Modern culture schools us to cover sensations with many layers of thought and emotion. Accordingly, we have a tough time dialing in to pure sensations.

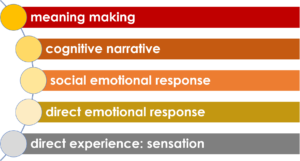

In last December’s Masterclass on embodiment and relationships, I offered a framework for the practice of embodying difficult sensations and emotions. This image represents the layers that cover sensory experience. We can “reverse engineer” embodiment by returning to sensation.

When something challenging occurs or is present within you, here’s what you can do.

The Three-Step Framework for Embodied Resilience

First, do a mind-body check in.

(For more information, you can view this article I wrote for Yoga Journal.)

Lie on your back with your knees bent, one hand on your heart and one on your abdomen. Close your eyes and breathe slowly through your nose as you explore the following nodes of self-inquiry:

- Are you present in your body in this moment?

- Can you feel the sensations of your breath?

- The ease or discomfort in your muscles and tissues? (It’s OK if you can’t; asking is the first step.)

- Notice the depth of your breath. Rapid breathing can signal nervous system overdrive. Slower breathing indicates rest-and-digest mode, which is conducive to setting healthy boundaries.

- Notice the speed of your mind. Do your thoughts channel surf? A speeding mind often means rising anxiety.

- Note any tension in your abdomen, home to your ENS, or “belly brain.” Tension here can change your gut microbiome, increase anxiety, and make it hard to set boundaries.

- Check in with the level of energy in your body. This will help you recognize when you are depleted and need deeper self-care.

- Bring awareness to your emotions: Are sadness, anger, or anxiety present? If so, do they feel like yours, or do they come from someone with whom you’ve recently interacted?

When you’re done, slowly open your eyes.

Choose a Practice.

This could be anything from “being with sensation” to connective tissue work. (Try the QL Release in the article linked above or one of our Restorative Yoga favorites, Face-Down Burrito Pose ) to the Empathic Differentiation exercise (see the same article).

Then, do another check-in.

What abides now? What remains? Here, you can do a little more “being with” practice. What remains present in your body after you’ve allowed time and space for reactivity? Does this bring fresh embodied (not mental) insight? Body resonance with the “other?” A change in your self-to-body relationship?

The idea here: Continue to move underneath the meaning-making, underneath the mental narrative, even underneath the social emotions. What do you feel? Where do you feel it? Does it change as you stay present with it? Sometimes it will change, and sometimes it will remain the same. Often, you’ll receive an image to work with, like the bird with flapping wings I referenced above.

The key: Continue to relate to what’s happening in your body without needing to understand it conceptually, or label it (a little labeling goes a long way), or act on it right away. Just keep going in, and in, and in, following your body. Remember to slow your breathing and relax your organs of perception (jaw, face, tongue, and mouth).

Repeat these steps whenever you feel activated or strongly entrenched in your views. This method also works well for interpersonal conflict, too. Just go through the steps when you feel activated in a relationship with a loved one.

Where We Go from Here

Despite how they can be “packaged” in the West, Yoga and Buddhism have always had a strong ethical focus. In both traditions, the most central ethical principle is non-harm. This speaks not just to the harm we cause directly, but the harm we witness (and don’t take action to stop).

When we can acknowledge the multiple challenges to the body sovereignty of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color, as well as gender non-conforming and other vulnerable bodies and join in actions to stop this harm, we access an untapped source of collective practice and power. This hidden dimension of body experience restores a missing piece of our humanity and with it a true sense of meaning, purpose, and belonging.

Drop me a line in the comments below and let me know how all this grabs you. As I have in my public teachings and Masterclasses, I’ll be talking more about the body as social and political in the weeks and months to come. Stay tuned.

Beautifully written with depth, clarity, and lived experience. Thank you! May I ask if you as a teacher set boundaries around the times that broader emotional, social or political discussions are appropriate for group Yoga classes or courses? They are not separate, I am aware, and yet checking in at the start of an asana or kriya practice can bring deep discussions that may trigger and not be fair to others who come to Yoga for peace of mind. We want a safe container for everyone. Inquiry into body feelings at the start of a Yoga class can open doors for great discussions, but can eat time for learning in some Yoga, Kriya, and other embodiment practices. Regular Ritual Yoga practices do not seem like the best time for Satsang. I teach courses and privates and write discourse where it IS appropriate and everything is welcome. But I am protective of a sacred field in classes. I hear your views as a writer, and would love to hear your views and guidance for teachers and students. How do you navigate this?

Thanks Marya. Personally, I set boundaries all the time as a teacher. These are threshold times; rather than stir up things in a process-ish way, which could be problematic, I read what’s in the room (for example, people’s bodies respond strongly to social stimuli and it’s often really clear when that’s happening- post-2016 election, for instance, and so many times since then). I don’t do much verbal psychotherapeutic processing, just a brief inquiry into what peoples’ bodies are asking for and then diving into the practice to address through somatic work. I might weave themes in through language throughout, while being mindful not to introduce material that’s not already present. So, very little verbal discussion. At the same time, while some may come to yoga for “peace of mind,” as you say, my goal is not to try to preserve and outer sense of peace when to do so requires denial or repression. Hope that’s helpful. Bleesings-

Very good article and well written. I agree with you about integrating body, mind, emotions, feelings, politics, social aspects, etc. into one subjective experience but we must understand that is our prospective either on a personal or group level. Discussing politics, or anything as far as that goes, is okay as long as we remain aware and conscious of our self (small self) and remain objective in the subjective world. But when we try to coerce, persuade or demand that someone else feel or believe the way we do, that’s when the ego takes over and the veils of imperfections appear while infinite wisdom drops away and the primal forces (gunas) remain in force. Practicing yoga is an art as well as a science as you well know. We must remain calm and true to our goal; that of reaching kaivalya.

Neil, thank you for taking the time to comment. I’m not sure about objectivity, but clear seeing is a good place to start. All the best to you.

beautifully explained

Thank you, Rebecca!

Bo,

Thank you for this deeply thoughtful and embodied well written post. I found it refreshing and nourishing. When it seems dangerous to even get out of bed, and like we will need activism to beat the band to survive what is or isn’t happening right now, well this was a wonderful reset to the day. I am deeply grateful for your great brain, your ability to process from sensation on up and your ability to share. thank you, keep up your work.

Marie

Marie, how kind. Thank you for commenting. I’m heartened to hear that my work and offerings are providing both nourishment and reset. There’ll be more. Blessings to you.

Hello Bo,

I disagree with the notion that you were wrong “mixing yoga and politics. I was heartened by your sharing your experience working during the election. This destruction of our democracy is unprecedented and I believe we all need to talk about politics. I grew up in a community like so many others where it is taboo to talk about politics; which perhaps has brought us to where we are today. Government and politics are necessary parts of our lives. Yoga is a necessary part of our good health and I personally benefit greatly from practicing every day. So you like other health experts need to speak about the vital connection between these basic principles of healthy living and wellness.

Thank you for sharing.

L

Hi Lin Thank you for taking the time to comment. Yes there is a destruction of democracy, one which echoes Germany pre World War II. Totally agree with you that we must talk about it, both because honest seeing is part of what it means to be embodied, and so we can right our course.

Dear Bo,

Thanks for sharing this and so much more over the years. I first saw you at the Toronto Yoga Conference, perhaps 2013? Since then I’ve employed what I believe you referred to as a “baseline check in”. It sounds like what you’re describing above. My yoga students and I have benefited from your blanket burrito as well.

The way you relate politics to our bodily responses is helpful to me, especially during this pandemic. The world has become a confusing place to inhabit. How fortunate to have your roadmap to inhabit the body.

Blessed be,

Penny

Hi Penny, Yes! This is a variation of the check-in, adapted for challenging situations. So glad you are finding this work helpful. Many blessings!

Bo please keep doing the work you have been doing and graciously passing it on to us.

My personal opinion; if ever there was a time for your cumulative work/knowledge IT IS NOW.

Thank you

Kathy Courtemanche

Hi Kathy, Thank you for taking the time to comment, and for your support. All the best to you!

Bo, This post is so rich with information. Having followed your work for so long, I always find new detail about the inner workings of our soma and our innate intelligence within us. I feel so at home when I read about interception or the ways we are disembodied as a society. I feel the truth, and relax down and in. I feel safe and supported and a sense of agency simply by reading and acknowledging what is true. You write the “hidden dimension of body experience restores a missing piece of our humanity and with it a true sense of meaning, purpose, and belonging” I feel closer to being a part of the solution as a somatic practitioner listening and being with all the ways we love and learn from our somatic intelligence. I continue today to step into action from my own innate wisdom and lean into the practice as a source of my innate resilience and capacity to trust in the highest good. I appreciate knowing the difference between stress response and stress resilience. Peace, Om Shanti Peace, Jennifer Degen